Ennio Morricone – In His Own Words

We don’t publish many book reviews on here (that might change), but this one has been long in the making. I finally managed to clear my head and schedule enough to just read the rest of this book by Alessandro De Rosa, which I had started way, way over a year ago after receiving it from the publisher. Ennio Morricone – In His Own Words is not a biography or autobiography of the recently passed maestro, but essentially a conversation. In over 300 pages no less, complete with footnotes, quotes, snippets of compositions even and color images.

Alessandro de Rosa (official website) is himself a musician, and from the start one must know that of course, this being a book about a composer, it is a book written by musicians, it is about music, and as such is sometimes a bit hard to read without much theoretical knowledge of music and composition. If you lack that knowledge, you will find yourself skipping a lot of pieces from the conversation, but since this isn’t a novel with a coherent story, it’s no big deal either. Having said that, I wanna state that I think you shouldn’t shy away from this book for this reason, as it offers plenty of insights into the person, his work and the movies he has enriched as well as the people he worked with.

This book accomplishes something that a biography (or autobiography) might most likely have failed at: to showcase, in a real conversation, not an interview set piece, Ennio Morricone as the intellectual and sharp thinker that he was. This isn’t a glamour piece about the rise and fall of a popular musician, or a trivia-ridden set of liner notes about the composer to your favorite spaghetti westerns. This is an exploration of the origins, thoughts and works of someone, who counts among the absolute best at his art, if not the best (looking at the Shores and Williamses of this world), and yet is no one trick pony.

Morricone is a true intellectual, someone with a wide array of interests outside and within the realm of music, a chess player, a chronicler of his contemporary times, a sought-after contractor – and yes, someone who is very well, soberly so, aware of his prowess and impact. He is a master craftsman and a professional, not an autodidact who happens to come up with some genius melodies every once in a while, like a singer-songwriter after a harsh breakup. I sometimes get the notion that especially in cineast circles, Morricone counts as “one of us” (whereas “them” are like serious composers of classical music or other high brow types), but he is an intellectual through and through, and it’s the low brow connotation that is the one that’s not truthful.

And there is another ingredient that makes this work unlike other works of its kind: it’s not a journalist, film scholar or ghost writer at work: it’s a fellow scholar of the art, a student and contemporary, engaging the maestro in conversation in a way that is never an interview, never a fanboy exchange, and yet doesn’t hold back in its admiration. It’s the relationship between Ennio and Alessandro that makes this book stand out, and even though I find the English translation, as good as it is, to be a sometimes overly wooden affair, often thoughtlessly directly transposing the Italian manner of sentence structure and mannerisms into English, where they sound off, it is a really easy read (the fact that I took over a year or two to do so has little to do with the book) and a very engaging text. It’s a conversation between intellectuals, about mostly intellectual subjects but on work and impact that goes well beyond the spheres of intellectualism – or even the academic realm, which has, as Morricone laments himself, thought of itself as something better for some time until finally opening up to his caliber.

Now, having read this from the perspective of a cineast first and an admirer of his music second (if that means anything), I of course particularly cherished the rich anecdoes and the treasure trove of first hand accounts sprinkled across these pages, as relating to motion pictures small and large, well and lesser known alike. And while his friendship and collaboration with the likes of Sergio Leone or Elio Petri take a center stage, the book offers so much more. Morricone is a cineast, and despite his intellectualism he is not above popular culture either, admitting to watching soccer games on sundays just the same as having Shakespeare theater subscriptions for his family. It’s his rich experience having worked with multiple TV and movie directors, that makes this a particularly fascinating way of learning about the industry: from the point of view of the sought-after composer. I found myself looking up a lot of titles on Letterboxd as I went through this tome.

Now if there are themes in de Rosa’s conversation with Morricone, then one of them I found most interesting is the frequent return to the question of where his life as a composer oscillated between composing original, absolute music and furthering his urge to experiment and research, and on the other hand his composing of film scores and other contract work. It seems to me Morricone has always tried to blend the two, and at times caused or suffered conflict due to conflicting interests when it came to music he was hired to do. Today he is credited with some notable advances in music and film scores especially, introducing sounds and instruments where there previously had not been such, and bridging – as I mentioned before – the supposed high with the supposed low brow elements of music. In that latter context especially it is interesting how Morricone himself describes his take on the commercial in his work, considering his financial safety no ealier than the early 90s and relying heavily on the support of his wife especially, but also his high output, especially in the 70s.

To conclude, this book offers many things, but a biography it is of course not. Students of music or musical history will find it too light on the details, whereas cineastes without background in music or composition will likely skim over many segments of the book. This, however is dangerous, as the two return time and again to examples and experiences in his work for directors, so the one cannot be separated from the other, even though the talk about musical motives, techniques and the study of snippets may mean little to most readers. Morricone: In his own words is a very rich intellectual conversation with one of the most impressive artists and practictioners of his time. It is especially enlightening to learn about the professionalism, intellectual curiosity and amibition he has always approached his work, balancing the composition for semi-commercial art films from Argento to Tornatore with his work in improvisation and experimental music, such as with the Gruppo Di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. In effect, I think most readers will take from this book that a lot of what Morricone is famous for outside of his audience of music professionals and scholars, rests on some false assumptions at worst, and on insufficient knowledge of his intellectual prowess and calbire at best.

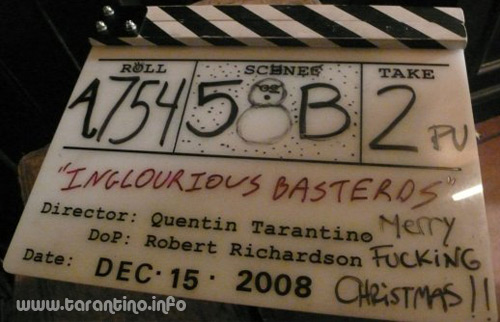

Lastly, when it comes to Tarantino, it is of course an interesting fact that Tarantino has used so many of his scores out of the original context, but I would like to interpret it this way: Morricone’s music has outlived and outgrown some of their original contexts, they have become timeless and ubiquitous to some degree, transcending media and art forms even, his style and motives having gained a life – and admiration – of its own. Whereas Tarantino is a scholar of cinema, and his work littered with hommages and quotations of other cinematic works, Morricone’s work is littere with musical references and innovations that are not based on accidents but just as well are based on him being a scholar and expert in music. In a way it is befitting that the two should have collaborated many times at least in Morricone’s late stage. Today, if you hear a Morricone score then, you may appreciate it on its musical qualities and merits, or on basis of its original application for example in a Dario Argento movie, or in a new context, let’s say Bill collapsing on his lawn.

I feel blessed for having witnessed the maestro live in concert twice, albeit at the very late stage of his life. I wouldn’t dare to even suggest that I know most of his music, in fact most people only know a tiny share of his output, but I can honestly say that cinema wouldn’t be the same without his compositions, and some of these put tears into my eyes every time I hear them in unison with the images that we’ll all remember forever just as much. Ennio Morricone has enriched music and cinema in an unmatched way, and while this is likely not the ultimate in-depth book about his work and life, it’s an outstanding book nonetheless and one befitting the great master. I wholly recommend it.

Buy the Hardcover (English translation): From Amazon.com – From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de – From Amazon.nl – From Amazon.se – From Amazon.ca – From Amazon.fr – From Amazon.com.au – From Amazon.es

Buy the Kindle version: From Amazon.com – From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de

Original Italian: From Amazon.it – From Amazon.fr – From Amazon.es – From Amazon.nl – From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de / French translation: From Amazon.fr – From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de / Spanish translation: From Amazon.es – From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de – From Amazon.nl / Polish: From Amazon.co.uk – From Amazon.de / Japanese: From Amazon.co.uk

Also check out this blog posts with music samples and quotes from the book: